Biography

Serlio, Sebastiano, 1475–1554, Italian Renaissance architect and theoretician, b. Bologna. He was in Rome from 1514 until the sack in 1527 and worked under Baldassare Peruzzi. Few traces exist of his buildings in Venice, where he lived from 1527 to 1540. Invited to France by Francis I, he appears to have served in an advisory capacity for the construction of the palace at Fontainebleau. He designed several châteaus in France; the only one that has survived, despite alterations, is that of Ancy-le-Franc (c.1546), near Tonnerre in Burgundy. Serlio's major contribution was his treatise on architecture (eight books, 1537–75). Intended as an illustrated handbook for architects, the volumes, separately published, were highly influential in France, the Netherlands, and England as a conveyor of the Italian Renaissance style; the treatise was also an influence in theatrical scene design and stage lighting. An early manuscript of it is preserved in the Avery Architectural Library, Columbia.

Central Perspective

His Architettura, published around this time, was the first Renaissance work on architecture to devote a section to the theatre. It also incorporated his theories on perspective, the art of representing three-dimensional objects on a flat surface. His many treatises included illustrations of the tragic, comic and satyric stages, based on Vitruvius’s innovative ideas regarding the vanishing point. Serlio’s sets are constructed in function of this point, at which parallel lines drawn in perspective converge. He was also the first to employ the term “scenography,” and to make extensive use of the scenic space and lighting to give the impression of depth. He did not limit himself to the painted backdrop, which was so popular at the time. With his technical innovations, Sebastiano Serlio had a profound impact on the theatrical architecture of his age.

"The greater the hall, the more nearly will

the theatre assume its perfect form." -Sebastiano Serlio.

The above is taken from the second book in Serlio's series entitled Architettura. He took what he was given in Vitruvius's De Architectura and created, in his eyes, the model for what a theatre should be. With his ideas and innovations, Serlio gave the Italian Renaissance the bridge it needed to start building its own theatres and expanding drama to the people of the period. He took Vitruvius and blended the idea of the true classical theatre with the art if the Renaissance and birthed central perspective into theatre. With that, he is able to transcend centuries as we are still using conventions engineered by him in productions today.

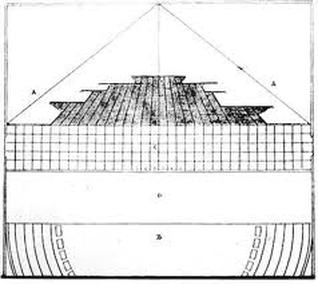

Serlio's contribution to theatre of his time has transcended the centuries and affects us today. He took what he was seeing in the visual art that had begun a few hundred years before. An artist of this period, Baldassare Peruzzi, had used the idea of perspective in his work. The image featured here is a work of Peruzzi (Absolutearts.com). If you look at this image and those we have of Serlio's designs, there are a lot of similarities. Take special notice of how the center of the image looks father away then the rest of the image, even though it is a flat piece. There is a point that is the farthest away is called the "vanishing point."

The way that the scenery was set up, the eye of the audience is to be drawn to that point. In addition to the idea of the vanishing point, Serlio used a raked stage. The performance space was level with the eye-level of the person seated in the chair of honor. However, after the performance space, there was a sharp incline in the stage floor, called raking. This added to the visual effect of creating a centralized perspective. It made everything upstage look like it was farther away than it really was because it was getting smaller.

If the use of these two things was not enough to create the image of distance, Serlio also used a series of wings to further draw the eye into the illusion. Usually, three sets of wings were used. Each pair was set in farther than the last. These began at the point on the stage where the actors did not perform. These wings not only added to the central perspective idea, they also allowed areas for the scenery and machines used for the spectacle in the intermezzi to be hidden.

Serlio's contribution to theatre of his time has transcended the centuries and affects us today. He took what he was seeing in the visual art that had begun a few hundred years before. An artist of this period, Baldassare Peruzzi, had used the idea of perspective in his work. The image featured here is a work of Peruzzi (Absolutearts.com). If you look at this image and those we have of Serlio's designs, there are a lot of similarities. Take special notice of how the center of the image looks father away then the rest of the image, even though it is a flat piece. There is a point that is the farthest away is called the "vanishing point."

The way that the scenery was set up, the eye of the audience is to be drawn to that point. In addition to the idea of the vanishing point, Serlio used a raked stage. The performance space was level with the eye-level of the person seated in the chair of honor. However, after the performance space, there was a sharp incline in the stage floor, called raking. This added to the visual effect of creating a centralized perspective. It made everything upstage look like it was farther away than it really was because it was getting smaller.

If the use of these two things was not enough to create the image of distance, Serlio also used a series of wings to further draw the eye into the illusion. Usually, three sets of wings were used. Each pair was set in farther than the last. These began at the point on the stage where the actors did not perform. These wings not only added to the central perspective idea, they also allowed areas for the scenery and machines used for the spectacle in the intermezzi to be hidden.